That’s all fine and well. I’m a perfectionist. It sometimes bites me in the ass, sometimes helps me achieve what I want to achieve. Often makes me stress out when I don’t want to settle for doing an OK job. I know others like this that struggle with the same things I do. And it’s fine as long as you are aware of and can control it.

Controlling it, though, that’s the hard part. It’s been over 2 months since I posted, and I have been working on a new post for over 6 weeks. It’s coming along slowly slowly (2 slowlys = a Malawian OVS inside joke). I’m looking forward to feedback on that one, because it concerns you. All of you. It’s about a theory I’m working on about one of the potential root causes of the development sector being so messed up, and also about the mental filters we use to make sense of the world. More on that later (how much later? Not sure…)

For now, because I don’t want to leave everyone hanging for 2 months at a time anymore, I’ve decided to just post an update as to what’s going on over here. With this post, I’ve decided to adopt a new regimen. No more than 3 weeks will pass between each of my posts, even if the posts are just quick, general updates as to what’s going on or some quick insights or questions. This is the plan, and it’s part of my personal strategy to change my own mental model: I’m trying to get out of the pattern of letting what I try to do perfectly be the enemy of what I could do well at the expense of doing other things adequately, or at all. Like blog posts. Or calls to the friends I love back home. Or maintaining my mental health. You know, that kind of stuff.

So, here we go: a new leaf.

Fishing lessons from a guy who’s never caught a fish.

It occurs to me that, in my infinite wisdom, I have neglected to actually explain what precisely I am doing in

Since November, I have been working with the Malawi Freshwater Project, a small, locally founded and operated Malawian NGO. Freshwater has been around since 1995 and has been under the leadership of Mr. Charles Banda the whole time. My role coming into the organization was to do leadership development work with Freshwater to help prepare them for an impending leadership transition. I won’t say any more details on that specific aspect of things given that this is the internet and all, but suffice it to say that the stated goal of my work was to help the upcoming leaders in Freshwater get to where they need to get.

For the first few months, I worked on what can be most easily referred to as “gap filling” activities. This is pretty common for first year OVS early in their placements: you just do what you can for the first while and try to understand as much as possible about your partner, their challenges, and their strengths. For me, that meant over 3 months of report writing, planning support, other documentation, field visits, and countless other things that I did because I was willing and able.

More recently in my placement, like the last month or so, I have been looking much more closely as “turning the corner”. I’ve got the village feather in my hat (sort of, more on that if you email me and ask), and I’ve learned an immense amount about Freshwater since I’ve been here. So, what’s next is for me to try to nail down what my “value add” is going to be for my partner. Right now, I’m looking pretty closely at working with Freshwater to develop a leadership development system that will help them develop the skills and abilities of their people even after I’m gone. Quoting my good friend Duncan Mcnicholl:

“Don’t give a man a fish. Don’t teach a man to fish. Teach a man to teach a man to fish, and his community is set.”

“Something like that” is what I’m trying to do at Freshwater. I’ve been working with people there the last while to

For those of you who are interested in the affects of gap filling on small NGOs and the other ways that you can approach organizational value adding, check out the 4 diagrams below I presented to Freshwater recently. The power was out in all of Chileka for 4 days so I used my time accordingly. I should take up sketching again I think, because my artistic skills seem to be dwindling.

Illustration of the starting situation.

Patronizing? Maybe a bit, but not so much in context. Would love to hear your thoughts on that. How would you react if someone presented this to you for your organization? Maybe I screwed up. Hard to say.

The "Gap Filling" Approach to external helping

The fact that this one is there sort of justifies image number 1 above, in my mind. The issue is quite real: when you are a high capacity volunteer working in a small organization with limited capactiy, gap filling can do a lot of damage. Maybe that sounds a bit big-headed, but that's not where it's coming from. I made a whole framework to describe what I mean there. Email me if you are interested or have thoughts on this.

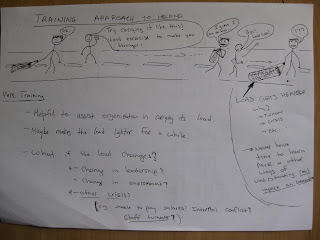

The "Training" Approach to external helping

Training programs and organizational development are not the same thing. I think training is really important for staff skills, but clear role definition and expecations are a must for such a role to be filled. Example: do you teach someone to use MS Excel, or do you teach them how to teach themselves to do it? Thoughts?

Organizational Development approach:

This is where the real meat of issues can get tackled. It's not so simple, though. An external volunteer thinking that an org needs OD is very different from an org reaching that conclusion themselves, especially if the external volunteer isn't necessarily right (which I'm not).

As things are now, I’m working on a couple of frameworks to structure my thinking as to what kinds of changes I’d like to see in Freshwater as a result of my “capacity building” placement there, whatever the hell “capacity building” really means. It’s one of those terms you can use to pretty much describe anything you want. Like how “sustainability” = “we will start the project and pay minimally, they you have to pay for the rest of your life.” Or how “demand driven” = “we will offer you a service so we can check it off our list of things donors want us to do, and if you don’t say ‘no’ then we’ll say there is demand for the service.” Anyways, that’s just a bit of jargon rant. Expect a strongly worded post elaborating on that at some point (When? Who knows.)

Anyway, some of the biggest things I’m focusing on, or hoping to focus on as my current thinking goes, are personal vision building for leadership knowledge, skills, and attitudes, and constructive relationship building. The latter point is a reflection of my assertion that organizations are not built by enhancing the skills of each person in a silo. You could train 2 incredible hockey players to be stars individually, and you could train 2 mediocre hockey players to play off each others’ strengths and work together effectively, and my money would be on the mediocre players.

Check out the frameworks below. Let me know what you think.

Building a personal vision:

Taking action towards it:

Not you vs. me, you and I vs. the problem:

Strategic Communication, not easy but necessary:

That’s pretty much the update in terms of work stuff. Hope you enjoyed it!

Go ahead, Demon from Hell, just try to possess me. I dare you. I double dare you.

Ahh, the home life. The last time I posted, I’d been living at my place for about a month. At that time, things were sort of weird, and I was at a bit of a loss as to what I wanted to share about it. At this point, things are substantially weirder, but I think that’s just the way it goes when you’re where I am doing what I’m doing.

I’ll start by introducing how I found the place. I’ve told the story of Odala already. The weekend after I met Odala, we went around all Sunday looking at villages looking for a place I might be able to live. My criteria were pretty clear: I didn’t care where it was as long as I was going to learn a lot and they didn’t speak English. After many hours of walking around and chatting, Odala went to his sister in law’s place, who directed us to someone else, who directed us to my place, which is called Kwasakanda. Asakanda is the guy who owns it, so the place is called Kwaskanda, and it’s in a village called Kwamapsuga, about a 25 walk (ish) away from the main road where the Freshwater office is located.

Odala and I met the kids who live there and the mother of the home, and we agreed on the price of the house I’d rent monthly. The issue was that the walls were not yet complete and the floor was not even started. So, the agreement was that Odala and I would go procure sand for them to finish it up and they would buy the cement. Then it would be 2 weeks for them to finish the work, and then I could move in.

So, Odala and I went to go get sand. I wasn’t too sure how to do that, but Odala said he knew a guy who knew a guy, so he borrowed my phone, made a few calls, and then we walked down to the river to meet a guy with a beat up old

That was the end of November 2008. It’s now March 28, 2009, and the work on the floor is not only incomplete, it hasn’t even started. This is just one aspect of the strange situation I am in with my home life. I live in a room inside the family’s main house. That means I eat with them, hang out with them each evening, and, amazingly, pray with them nearly every night for about 1 or 2 hours. I’m not religious, and the family knows that. When asked which church I pray with (a very common question in

Evelynne- The mom

I call her “Amayi”, meaning “mother”, but it’s also just used as a respectful way to address a woman. Evelynne and I have a really interesting relationship. She’s the matriarch of the home, the bossy Malawian mom. She doesn’t speak any English, and speaking to her is always an adventure because, since she is completely not used to speaking with people that don’t know fluent Chichewa, she gets really impatient really quickly when I can’t understand what she’s saying. At first it bugged me but these days, after 3 months of the same thing every single day, I’m starting to get used to it and figure out how to deal with it. She tells me what to do all the time: what to wear, when to shave, when to wake up. If I try to leave the house with shorts on, I have to do it stealthily lest she notice, and when she notices, all bets are off. I have to change into trousers.

Evelynne is also really funny and always laughing. After dinner, if the family eats mandasi (Malawian mini-donuts) for a snack, she makes me eat some and says, “Aphiri, Musangalale!” with a laugh and a smile. She is always smiling, and almost always laughing. She makes fun of her kids a lot, and I go along with it because it’s pretty funny. Nowadays, as my Chichewa is getting better and better, we are able to actually talk a bit more. It’s really interesting to talk with her about the things she is passionate about, which are mainly God and the defeat of witchcraft in

Asaladi- The dad.

I call him “Abambo”, meaning “father”, but it’s also just a respectful way to address a man. He sells cement in

Ndaziona - the younger daughter

Ndaziona, or Ndazi as we call her, is the 15 year old daughter of Amayi and Abambo. She and I get along really well. She has the same infectious smile and laugh as her mother, and we are always joking with each other. “Joking” is an interesting term to use because all of our interactions take place in Chichewa, and my ability to make jokes in Chichewa is pretty limited. I think the better description may be that we screw around and say stupid things, which is funny for her because she’s 15 and funny for me because it’s another aspect of the craziness of my life right now. Here she is:

Check out these videos below that Ndazi and I made today with the other kids who live beside us.

In this one below, the cute small one is Gertrude. Her older sister, to the right, is called Manis, and the boy at left is Leko, whose name I forgot and Ndazi had to remind me. Ndaziona strolls by the screen at the end.

In this next one, the dialog is roughly as follows:

Me: Well, now you’ve stopped recording, so you want to start again.

Ndaziona: Mmm.

Me: Can I see it? Oh, OK, leave it like that. Now you can choose what you want to record. Children!

Ndaziona: Should I press here?

Me: No. You see the letters that are red, “REC”, that means that it’s already working. Remember that we already made the video before? It’s working now, like that. Yes.

Chinsisi - the son

Chinsisi, sometimes called Sisi or Chisisiewe, is the 14 year old son of Amayi and Amabo. Chinsisi is a real character. He loves to dance, and really loves to pray. Most nights before he goes to sleep, which is the room next to mine, he literally yells at God for about 10 or 15 minutes praying. I’ve heard him praying for me, for Joyce (the house cat that I named and was previously named “Phusi”, which means “cat”, but who sadly died), and for the rest of the family. He’s a cool young man whom I am happy to know and who it’s fun to bug. He also doesn’t speak any English, but between us the communication seems to be easier somehow. I think it might be because he tends to leave me alone more readily when it’s clear I don’t understand and don’t feel like trying to. Think about it: if you lived with a family who didn’t speak English but who was very demanding for you to know their language, would you ^^always^^ feel like straining your brain to figure out what they’re saying to you, especially if they talk quickly and colloquially? I’m trying hard, and I’m succeeding, but a guy needs a break every now and then.

Anasi - the first born

Anasi, or Alice, is the first born daughter. She's about 17 and currently isn't around all that much because she's going to school in Lilongwe. She speaks English quite well, or rather she can speak English quite well, but we always speak Chichewa at home anyway. Since she's not around I haven't talked to her too much, but she is another kin to the smiling and laughter that Ndazi and Amayi bring to the household. She recently finished form 4, which is equivalent to finishing high school, and now wants to study nursing. She's quite delightful, but definitely got the bossy genes from mom. She's also the most critical of my Chichewa. She's quoted as saying:

"If you make a mistake once, you should learn. Once you have learned, if you make the same mistake again, you are not trying. Try harder."

This was said in Chichewa of course, quickly, and after about 2 weeks of my living there, so it took a few iterations for me to figure out what she was saying. Gotta learn somehow right?

Aphiri the Preacher, AKA Abusa

Abusa, meaning “preacher”, or Aphiri as I call him, which is his clan name, is the uncle of Abambo. This is a bit weird because he is actually substantially younger than Abambo, but I’m not about to try to figure out the family tree. Aphiri explained it to me once: it’s something to do with one of their parents having lost their spouse then remarried, but it’s not quite clear.

Most nights, Aphiri comes by the house to help the family pray. They do not mess around with their prayer in my house. The family is very, very religious. I have been praying with them at night, and though they know I’m not religious, they welcome me anyway. It’s a very interesting experience and it basically serves as my daily Chichewa lesson. They often read Bible passages and sometimes make me read them, and indeed translate them into Chichewa because they want to test if I’ve understood. Consider this: Leviticus Chapter 6 Verses 8 to 12:

"The LORD spoke to Moses, saying, 9"Command Aaron and his sons,

saying, This is the law of the burnt offering. The burnt offering

shall be on the hearth on the altar all night until the morning, and

the fire of the altar shall be kept burning on it. 10And(K) the priest

shall put on his linen garment and put his linen undergarment on his

body, and he shall take up the ashes to which the fire has reduced the

burnt offering on the altar and put them(L) beside the altar. 11Then

he shall take off his garments and put on other garments and carry the

ashes outside the camp to a clean place. 12The fire on the altar shall

be kept burning on it; it shall not go out. "

Right. Try translating that into Chichewa.

Aphiri and I are friends, I think. I have been giving him guitar lessons for some time now, and he’s getting pretty good. One thing that amazes me about people here as how great their sense of rhythm seems to be. This comes in handy when learning guitar. Aphiri wants to learn the guitar so he can play music in the church when he gives sermons. I’ve taught people to play before, and one common complain I often get is that peoples’ fingers hurt when forming chords. Not Aphiri. His Malawian hands are tough as leather, and we can play for an hour without him saying a peep about his fingers. This is a Malawian thing I think. This is the same reason that they can take handfuls of steaming nsima in their hands no problem, but I feel my skin burning every time I try it. And I thought I had a pretty high threshold for pain.

When my sister, Sylvia, was pregnant (she had her son, Charlie, about 5 weeks ago), I told the family about it, and that led us to do a night of prayer for the safety of Sylvia and her unborn child about 2 months ago. We all held hands, closed our eyes, and prayed that mother and child would be safe and healthy for about 20 minutes. Aphiri led us in the prayer and yelled his pleas to God for their safety. They did that all for my family because they wanted them to be healthy. This was pretty awesome, and I can't wait to tell Charlie that story when he gets older.

Check out the video of Aphiri below. Rough translation of the conversation:

Aphiri: But I’m not wearing good clothes! (before movie begins)

Me: No problem, you look good. How did you rise?

Aphiri: I rose well, how about you?

Me: Well thanks. This one is my friend Aphiri, who I am teaching to play guitar.

Aphiri: True, yes.

Me: And he’s teaching me to pray.

Aphiri: To pray, yes.

Me: So, he’s my friend. Thanks Aphiri! I can show the video I just made to my family in

Aphiri: Thanks!

Me: Thanks.

One thing that’s a bit unsettling about this relationship is that, even though the family knows I’m not Christian, I think they are trying to convert me. Aphiri and Amayi are constantly telling me that I need to pray back in

Things recently got kicked up a notch with the whole prayer situation. A few weeks ago I asked Aphiri to explain to me what he meant when he said “Roboshoka rakashakmamaba…” and other things like that that he says, or rather yells, during prayer. He LOVED this question. See the video below to find out why. Apologies in advance for the profanity: when I made that video I was a bit freaked out, which I think comes through in a number of ways. I think maybe Aphiri thinks he’s saved my soul. Hell, maybe he has. What do I know anyway?

My name in Chileka is not Mike, it’s Aphiri. Alex from work gave me that name back in December as a joke indicating his view that I was becoming Malawian, mainly because of the way I was speaking Chichewa with the guards at Freshwater. I began answering to that name at work, and within a few weeks, it spread like wildfire around town. Now everyone in Chileka knows me as Aphiri, and nobody calls me Mike. Not at home, not at the market, not even at work. Everybody calls me Aphiri, and in fact most don’t even know my real name. Even the minibus driver who looks like Cuba Gooding Junior, with whom I’ve never spoken, calls me that. Every day I walk down the street and am greeted by my Malawian name by people I don’t know. It’s pretty funny, and it would be weird for me now if I went and lived somewhere else in

I’m not in the slow lane, not in the fast lane, I’m in the lane where my speedometer doesn’t seem to be working. I’m learning a lot here, and sometimes I feel like I’m accomplishing a great deal, while at other times I take a look at what I’m doing and ask if it has any value whatsoever compared to what I would have been doing if I never moved to Malawi. The first 4 months have been really tough, as I have explained. But things are changing. It’s not clear how they are changing, but I can say that I am looking forward to the next months of my life here being different than the first 4 months. Things are about to come to a head at work (how friendly the face of this head will be remains to be seen), and I am going to start connecting with the other members of the team a lot more than I did in the first 4 months, which was virtually not at all. I’ve had my desert island experience, now it’s time for a change of pace. How precisely that will manifest itself is not yet clear.

I've been writing music again but am having trouble nailing down anything I like. Also been reading like crazy. Some novels, lots about organizations, too. I just started a really interesting book about Canada's role in Afghanistan called "The Expected War." Days are characterized by walks through to mud to and from work, rice, nsima, or chips for lunch, perpetual candle light at home when it's night time. Lots of praying (which is really wierd to see myself write because I'm not religious), lots of Chichewa, lots of learning.

Continuing the Odala Saga

Not too much new to report here really. Odala has bought a phone, which is good because that means he must be saving some money from his teaching activities. He’s recently opened a private nursery school. He has no qualifications as a teacher, but he went and bought some books and teamed up with a university graduate, and is now running a school. Not to sell Odala short, but he’s no teacher and neither is his friend, so it makes you wonder about the quality of the private schools in

I’ve started doing computer lessons with Odala, and am still waiting to hear what’s gone on with him and his brick selling. He was supposed to sell the bricks a month ago then use the funds to start the DVD business, but it’s all up in the air right now I think. Anyway, that’s about all for now about Odala.

We can put ‘em in the ground, but we can’t keep ‘em working

The EWB Southern Africa WatSan team is in the process of hashing out a new strategy right now. There are two main prongs to it: Hygiene and Sanitation Behaviour Change, and Water Point Functionality. This new strategy represents an unprecedented level of focus for our team: we are going to start really thinking about who we partner with so that we can identify change paths where we can find multiplicative change impacts, like the concept of transformative change. There’s an underlying evidenced based principle that’s going into each of these areas of focus. For HySan Behaviour Change (HSBC, really) the idea is that CLTS (Community Lead Total Sanitation) is a pretty viable approach, and we are going to focus on it NOT because we think it’s the greatest thing ever, but rather because it will be a good vehicle to learn how to create change in the whole HySan sector, which is a complicated one that has seen limited success. For Water Point Functionality (WPF, which is confusing because WFP = Water For People and FWP = Freshwater Project), the idea is that, yes, implementers are succeeding in getting boreholes into the ground, but the problem is that functionality is not reliable. This is meant to be addressed by VLOM (Village Level Operation and Maintenance) which is supported by CBM (Community Based Management) training, which basically works to train communities on how to use and maintain an Afridev Pump Borehole.

The problem (well, one of them) is that CBM is basically not really working. Supply chains for spare parts and trained labor as well systemic accountability for borehole operation and maintenance are weak in

You may ask (or maybe not, I won’t put words in your mouth): why can’t they just maintain the borehole themselves? I mean, it’s their asset, right? Why don’t the communities just suck it up and figure it our? Consider this anecdote I wrote in a report to EWB a while back:

Remember that random theorem you learned 4 years ago back in Math 200? Well, today you’re going to need it.

At the CBM training in Mozeni/ Jose, villages in Chikwawa District, I observed the ways in which the community is exposed to the ideas of leadership, fundraising, borehole ownership, hygiene and sanitation, and borehole maintenance. There was a lot of stuff crammed into a 5 day course (8 AM to 1:30 PM each day), and not everyone was present nor engaged for the whole thing. There were a few stars though: people who were really involved and clearly trying to learn the material.

The workshops were not really participatory, though the Community Development Assistant (CDA) who talked about fundraising, committee roles, and leadership was fairly good about this. The Water Monitoring Assistant (WMA) was really barking at the people as though it were a boot camp, however. I sat with the committees on their benches for a couple of days of the training to get their view of the event (I was sitting with the facilitators for the other days). One thing that struck me is that, if this were a university lecture, I might say that the prof was pretty good in that he was high energy. But, in an adult education atmosphere in which people were supposed to be learning how to care for a livelihood asset, I felt myself being critical of what I was seeing from the WMA. There was little space for questions and not any kind of atmosphere in which I think people would feel comfortable saying they don’t understand what was going on. Stepping back, I tried to find things about it that didn’t blame the attitude of the WMA (who was definitely a bit of a big bwana), but more looked at the overall approach of the trainings themselves.

I thought about it like this: imagine someone came at you with literally dozens of pages of pre-made flip chart text (with instruction sets with as many as 21 steps in them), and you were expected to take notes in notebooks and understand how to do something quite technical. Imagine the topic was how to change brake pads on a Land Rover, and there were some diagrams, etc. Now imaging you drive the Land Rover every day for 3 years but never practice or have any follow up on the brake pad lessons, then one day you need to fix them. You took notes on some flimsy notebook 3 years before and are expected to remember how to jack up the car, take off the wheel, remove the worn pads, and finish the rest of the 10 or so steps you learned a while back. If I had never changed brake pads or driven a car before, I think that would be a tall order for me, and I am a technically inclined university educated engineer who is used to writing and learning in that kind of context and is used to keeping notes.

Maybe I’m overstating this issue a bit or not giving the villagers enough credit (for example, maybe they take the responsibility to practice the skills they’ve learned every few months so that they don’t get rusty), but, given that so many boreholes are not functioning in Malawi, I feel that the quality and approach of the CBM training needs to be really examined.

There are questions about this story at the bottom of the post, and much more to come in terms of interpretation in a later post. For now, any thoughts you have would be much appreciated.

Stirring the political pot to thicken the political plot

As before, I’m not going to post any updates on the political situation in Chileka right now. But things are getting interesting, so, as before, email me if you’d like to know the scoop. May is going to be a very interesting month.

Questions for Thought and Reflection:

I’m interested in hearing reactions to the story I told about the CBM training in Chikwawa. If your water main breaks in

Now imagine you don’t pay taxes because you are too poor and your country’s government can’t enforce tax laws anyway. What does that change about the situation, if anything?

What would need to happen in your life for you to actively take charge of operating and maintaining your own water supply? I’m not just talking about doing what your told, either. I mean forming a community committee, going to meetings, fundraising, and actively scheduling and/ or carrying out maintenance and repairs for your water system. Thoughts?

I remember reflecting on this with my friend Anna-Marie back when there was the garbage strike and trash was piling up everywhere. I seem to recall that, when people started to take charge of their own public service and move some of the trash (voluntarily I believe) people told them to stop because it was helping the City to shirk their responsibilities. So it seems to me that it's all to easy to assume that simply telling people they are responsibile for something will allow people to take control of it; in fact, judging by our Vancouver trash example, some are even of the polar opposite mindset. What am I missing here? What do you think?

Thanks for reading!

~MK

2 comments:

In the spirit of not letting the potentially great in the way of probably adequate I am going to throw down some thoughts and start up the discussion! In response to"What would need to happen in your life for you to actively take charge of operating and maintaining your own water supply? " I have a story! So my dad is from a small village in south of Iran with hot semi-arid climate. The village had a water distribution system but the water provided by the distribution system wasn't potable. To maintain their drinking water supply, the people in the village built their own protected rain catchers/ reservoirs (I don't know the English name for them!) and maintained them and they also bought water filters or water treatment at the household level. The community also built their own school and health centre.

Why did the village take charge? This is from a teenage Sara point of view: the village had the means to do so. The village is/was relatively rich (many men in the village work overseas and send money home) . So they had resources beyond what the government was going to allocate to that village and the villagers wanted a quality of life beyond what the gov't was ever going to provide for them.

There were a few big families in the village that used to own a lot of the land in the village and also rule the village in sense. They took initiative and lead some of the above projects. I guess, them championing the project was their way of giving back to the community or their way of keeping their "approval rating" up in the village.

The village population is part of a minority group in the province (different dialect and religion background than the rest of the province and the provincial government). The minority group is well know for supporting itself (a supportive culture and network)!

I don' know how helpful this is to the southern Africa team but within my village's context : need, means (money and manpower/expertise), lack of expectations from govt, local project champions, and support networks contributed to the village taking on its own projects successfully.

Thanks for you thought provoking blog and thanks for all the stories and pictures!

Hope all is well in Malawi!

Great post again Aphiri-Kang.

Thanks for bringing everything back to allow me to see the problem through Canadian experiences. Such a great clear explanation of the issue.

I'll probably use this as a a basis for my own training coming up - but I'd love to hear CBA-updates as your work continues!

Post a Comment